Itzhak Luvaton

'CHAINS OF SILVER' EXHIBITION

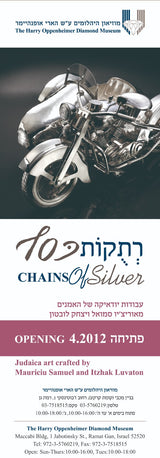

The special works displayed in this exhibit "Chains of Silver" are those that at first glance lack Jewish context. The solar system, the “trendy” motorcycle with a sidecar, a vintage luxury car, an airplane based on a model of one of the first planes, a tank or a train… they are not specifically identified with the Jewish world. On the contrary: many of these items are symbols of a materialistic culture that is considered the complete opposite of tradition, particularly of religious tradition.

It is therefore so surprising to discover that each of these items that we call “modern” and “symbols of progress” hide within them Jewish ritual objects.

The inspiration for creating these items is found in the expression “the hidden is greater than the obvious” that prevails in many spiritual philosophies that cannot be elaborated on here. What’s important to stress is that hiding religious artifacts is not an time. At various times and in various places, people or communities that felt threatened if they performed their rituals openly tended to hide them. (For example, the Huguenots, the Freemasons, the Druze, etc.) Starting in the 15th century, we come across the phenomenon of the Anusim, who out of fear of the Inquisition kept their Judaism hidden, camouflaging their traditions and their internal essence to ensure their continued Jewish existence.

The recent personal history of one of the artists featured in this exhibit demonstrates the necessity of concealing Jewish ritual items. After World War II, Mauriciu Samuel’s father was an enthusiastic communist in a silversmiths’ cooperative in Romania, and even served as the president of the cooperative in Bucharest. For political reasons, he was prohibited from creating items with a religious orientation without approval from the party.

When he understood that he could not realize his aspirations as a Jewish artist, he built himself a workshop in his kitchen in Bucharest, where the shelves and drawers hid an entire workshop where he fashioned Jewish ritual items.

Traditional Judaica works that integrate the routine life of the 20th century contain a kernel of surprise, but also serve as a declaration, calling to the viewer to look for the deep roots of each work, even if it looks like something made yesterday.

Fashioning Jewish ritual objects presents a challenge. First and foremost, it is a Halachic challenge, because the art must submit to a rigid framework of rules that have been formulated over centuries. Another challenge is to ensure that although the artist is using a well-known, and sometimes clichéd, symbolic language, he does not slip into the flat, two-dimensionality of an advertisement.

Another issue is the need to appeal to emotions, to one’s deepest senses and feelings, since the item is supposed to express the connection between the user and his Creator and his faith. In such a case, the artistic object must create an emotional structure that befits the occasion.

If we add to all of the above a special and unique creative-artistic element as well as a practical element, we begin to understand how much artistic imagination, geometric thinking and technical skill went into fashioning the Judaica items before us. And of course, there must also be love. Just as with any work of art, there must be a love of the idea and of art; without such love the silver would remain a cold, gleaming, meaningless sheet of metal. (from the cataloge "Chains of Silver", Curator: Yehuda Kasif)

Itzhak Luvaton is a Judaica artist who was born in 1963 and grew up in Tel Aviv. After completing his military service in a paratroopers unit with the rank of captain, Luvaton turned to learning jewelry making and design at the Omanit school in Jaffa, with Meister Guy Kristin. He trained with the master engraving artist Yasha Ben-Zion on various subjects of smithery, and completed his training in the field of hammer work at the Betzalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem with master artist Karol.

Itzhak Luvaton’s unique Judaica work combines ancient and traditional Jewish symbols with contemporary modern design In his work, Itzhak commonly combines silver with other materials, including exotic woods, gold and aluminum.

His creations are displayed at his Itzhak Luvaton Gallery in Jerusalem, at many museums and other galleries throughout the world that hold fine Judaica exhibits. Many collectors boast his signed works of art.

Mauriciu Samuel is a silversmith and Judaica artist, the third generation of a family of smiths. Mauriciu Samuel was born in Bucharest in 1957, and immigrated to Israel with his parents in 1959. As was customary at the time, the art of smithery was handed down from father to son. After the family’s immigration to Israel, his father opened a small workshop in central Tel Aviv, where his mother also contributed her talents as a designer and painter. Mauriciu learned smithery from his father, Meister Samuel Leo, of blessed memory. He was trained professionally in engraving and etching with master artist Yasha Ben-Zion, and apprenticed with master artist Pinko Solomon.

After completing his civil engineering studies, he enlisted in the IDF, and completed his service with the rank of major. In 1986, he began working in the design and creation of Judaic art.

Traditional content characterizes his work, alongside the techniques used by silversmiths throughout the generations. Samuel designs works that are unique and exclusive, bearing ornamentation, pictures, drawings and segments of passages from biblical sources, and which are executed mainly through hammering with a smith’s hammer. Along with more traditional Judaica items, his education and family and personal background enable him to design Jewish religious artifacts that are accepted as three-dimensional creations with outstanding technical characteristics that are frequently taken from the material world around us.

His works are found among the most prominent Judaica collectors, at well-known museums, and in synagogues throughout the world.

The paths of these two artists crossed in 1986, when both studied etching under Yasha Ben-Zion. Since then, they are friends and artistic partners in the field of Judaica, a fruitful relationship that has succeeded in blending east and west in their unique, original and useful ritual items.